I recently came across a book that’s been out for over 10 years by an exceptional and tenacious researcher and an engaging writer, Lodewijk Petram. His book, The World’s First Stock Exchange, might be the first to explore how early investors bought and traded shares of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). In this conversation with the author, we learn that complex trading techniques did not start in the modern era–far from it.

Interview Highlights

- A reason to study history and a nudge from Liddell Hart.

- There is nothing new under the sun except for a bit of technology here and there.

- The book that has not been written before on this topic.

- The story behind Confusion de Confusiones.

- The merchant, the philosopher, and the shareholder.

- Yet, they still invested, including a poor maid.

- The original 1,143 investors and the purpose of the capital raised.

- The way the Dutch East India Company made money.

- Unique monopoly power.

- Forward contracts and naked short selling in the 1600s.

- Stories of fraud.

- Would Buffett and Munger make this investment?

- How the stock price behaved in the early years.

- Investment lessons for young people.

- Book shoutout: Buddenbrooks: The Decline of a Family by Thomas Mann.

Lodewijk Petram’s award-winning history demystifies financial instruments by linking today’s products to yesterday’s innovations, tying the market’s operation to the behavior of individuals and the workings of the world around them.

I Did Not Know That – Five Insights From The World’s First Stock Exchange

Lodewijk’s book answers questions that Confusión de confusions does not, such as how the early stock market worked and how it developed so quickly. However, I wasn’t even aware of the de la Vega book until I read Lodewijk’s. That’s surprising based on this line in the book:

In 1995 the Financial Times published an article in which the editor picked Confusión de confusiones as one of the ten best books on investment ever written, describing it as a guide for modern investors. Page 10

I would have enjoyed seeing financial results for each cargo brought back safely for eager merchants to purchase for soon-to-be buyers. I’m sure that data does not exist. However:

Not every vessel returned to the Republic of the United Provinces, but those that did were laden with highly profitable cargoes, and the costs of the expeditions were recovered several times over. Page 17

Short selling in the 1600s, seriously?

We do know that share dealers revived the practice of naked short selling before 1623, because it was in that year, when the Company’s charter was renewed, that the 1610 edict was promulgated again. It contained a few additions. For instance, “renouncing the edict directly or indirectly” was prohibited. In other words, dealers were not permitted to relinquish their rights under the 1610 edict or the new one, which came into effect on June 3, 1623. Putting it another way, traders were not allowed to agree that their dealings in nonexistent shares were valid. The fact that this was explicitly stipulated indicates that it had meanwhile become standard practice among the traders. Pages 108-109

As an equity investor, I read many financial reports and I get my money’s worth from Seeking Alpha. Yet, VOC investors received no financial data. They could only look forward to learning about ten new dividend payout.

The shareholders were obviously interested in the size of the dividend payment because it determined how much money or spice they would be able to collect from East India House. Even more important, though, was how the dividend related to payments in previous years. The share dealers could deduce from this how well the VOC was doing. If the dividend was higher than in previous years, it meant that the Company had more cash and that profitability had improved. A drop in the dividend, on the other hand, was not good news. Page 171

Why was capital needed from the public when it had never been before from any organization? The answer is intuitive:

The fact that there were no companies other than the VOC and the WIC with publicly tradable shares during the seventeenth century was attributable in part to the scarcity of enterprises with such a great need for capital that issuing shares was worth considering. Large machines, for which substantial funds would have been needed, had not yet been invented. Even breweries, a sector with a demand for capital above the average for the times, were able to manage on finance supplied by the owners, with additional loans if needed. The VOC and the WIC were clear exceptions in the Republic—large organizations with thousands of employees, huge warehouses, and a big fleet at sea. Pages 255-256

Important Links

- Lodewijk Petram LinkedIn profile

- Lodewijk’s book website

- Personal website

- Additional biography of Lodewijk Petram

Episode Pairings

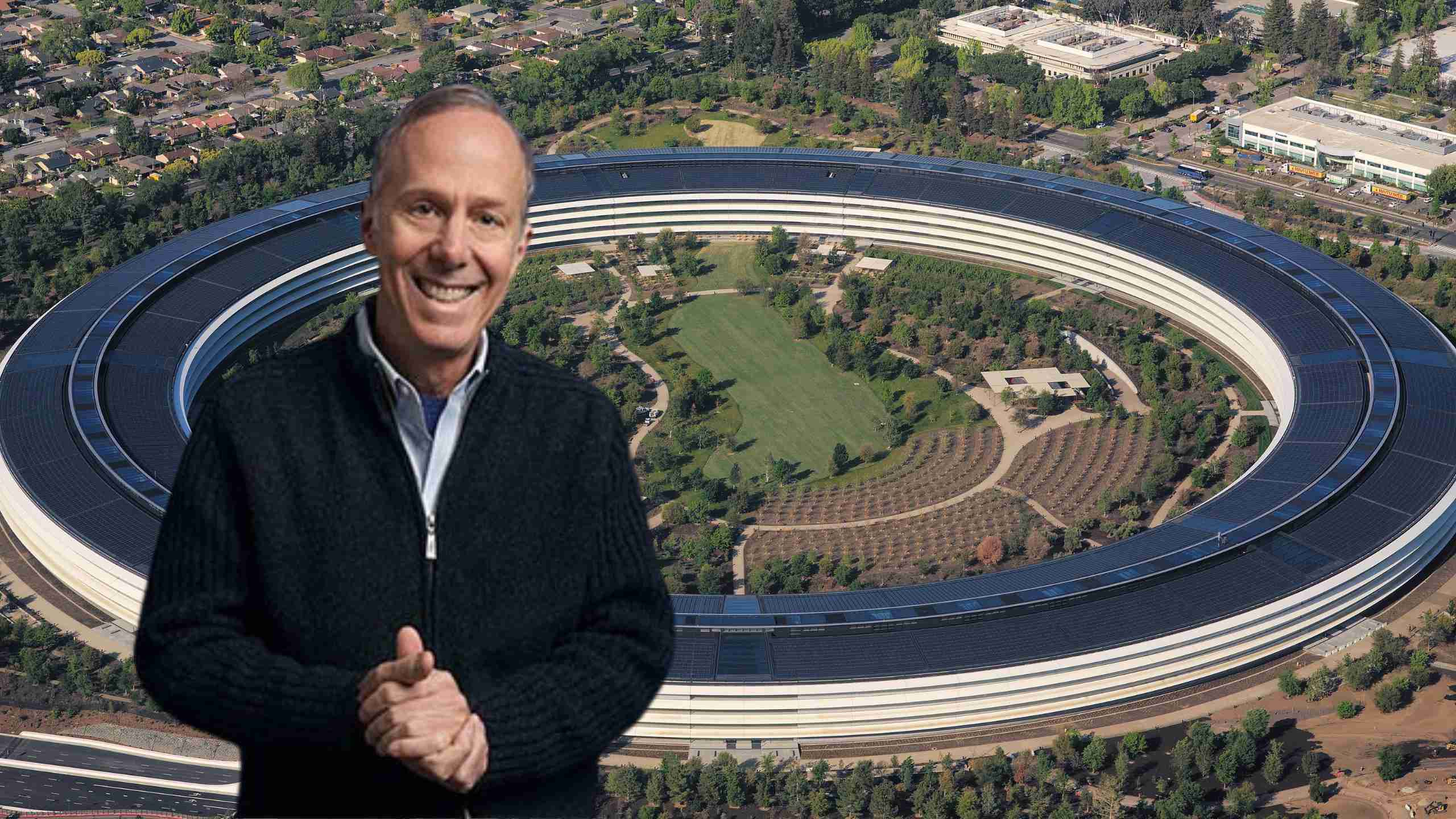

Title Image Credit: Wikipedia Commons

Leave a Reply